Sometimes the greatest musical influences aren't the music or artists, but movements that capture a moment and change everything that comes after.

Sound system culture is one of those movements. It fundamentally changed how we think about DJing, production, bass, and what it means to rock the crowd.

The lineage traces back to post-war Jamaica and brought us everything from hip-hop to jungle to D’n’B to dubstep and much more.

Let’s walk through the history of sound system culture and its huge impact.

- The Birth of Sound System Culture

- Kingston's Mobile Bass Revolution

- The Studio Becomes an Instrument

- The Windrush Generation Brings Sound Systems to Britain

- DJ Kool Herc and Hip-Hop's Jamaican DNA

- UK Bass Music: The Second Generation

- Free Parties and the Illegal Rave Movement

- The Legacy Lives On

The Birth of Sound System Culture

After 1945, thousands of rural Jamaicans flooded into the city in search of work.

The economy was unstable, live music was expensive, and most people couldn't afford to buy records or attend the jazz orchestras playing for Kingston's wealthy.

The solution? Load a truck with a generator, turntables, and massive speakers. Set up on any street corner. Charge a small entrance fee. Let the music do the rest.

These were the first sound systems.

Early pioneers like Tom the Great Sebastian (run by Chinese-Jamaican businessman Tom Wong), Duke Reid, and Clement "Coxsone" Dodd turned sound systems into proper businesses.

They'd travel to the United States, buy stacks of American R&B records that weren't available in Jamaica, and bring them back to Kingston's crowds.

Competition was fierce. If you had the best records and the loudest system, you controlled the dance. Sound clashes – informal battles in which two systems set up near each other and competed for the crowd's attention – became commonplace.

The practice of "rewinds" – when a DJ pulls back the record and restarts a track because the crowd's reaction is too intense – originates from clash culture.

Duke Reid, an ex-policeman, was known for firing revolvers into the air while playing his sound system.

The connection between gangland culture and sound systems became stronger, though most operators stayed focused on the music itself.

Kingston's Mobile Bass Revolution

By the mid-1950s, custom-built speaker systems started pumping the levels.

Hedley Jones, a former radar engineer from the British Air Force, opened a radio and record shop in Kingston. Using his severance pay and his knowledge of electronics, he built an amplifier that separated frequencies into three bands: bass, mid, and treble.

Jones would play music outside his shop to attract customers, and spontaneous street parties would form. His amplifiers, nicknamed "Houses of Joy," became the template for the massive speaker stacks that defined sound system culture.

As rock and roll started dominating American radio in the late 1950s, the supply of R&B records dried up. Rather than fold, sound system operators started making their own music.

Coxsone Dodd began recording local musicians in radio studios, creating what became known as "Jamaican boogie."

By adjusting the rhythm structure of American R&B and emphasizing the second and fourth beats, Jamaicans developed the off-beat skank that would later define classic ska and other genres.

Old-school Jamaican Boogie

These early recordings were dubplates – exclusive acetate discs cut for a single sound system.

Why press multiple copies when your competitive edge depended on having music nobody else could play?

The Studio Becomes an Instrument

King Tubby had a huge impact on electronic music. Born in 1941 as Osbourne Ruddock, he was an electronics technician who repaired radios and built transformers for sound systems.

In 1968, he started working as a disc cutter for Duke Reid at Treasure Isle studio.

When asked to create instrumental "versions" of songs for sound system MCs to toast over, he started experimenting. Rather than just removing vocals, Tubby began manipulating the mix itself.

Using the MCI mixing console he'd bought from Dynamic Studios, Tubby pioneered techniques and effects that became dub music's signature:

- Echo and reverb: Using tape delay units and spring reverb to create vast, cavernous spaces in the mix.

- Dropouts: Completely muting instruments, then reintroducing them suddenly.

- EQ manipulation: The console's parametric filter allowed Tubby to sweep frequencies until they disappeared, a classic live effect used widely today.

- Playing the desk: Tubby treated the mixing console like a musical instrument, bringing faders up and down in real-time, creating performances rather than static mixes.

Kickstarting the art and practice of remixing, Tubby was creating entirely new compositions from existing recordings.

By the end of 1971, he was providing dub mixes for producers like Glen Brown and Lee "Scratch" Perry. The artists he collaborated with include Augustus Pablo, The Aggrovators, Yabby You, U-Roy, and The Wailers.

The Windrush Generation Brings Sound Systems to Britain

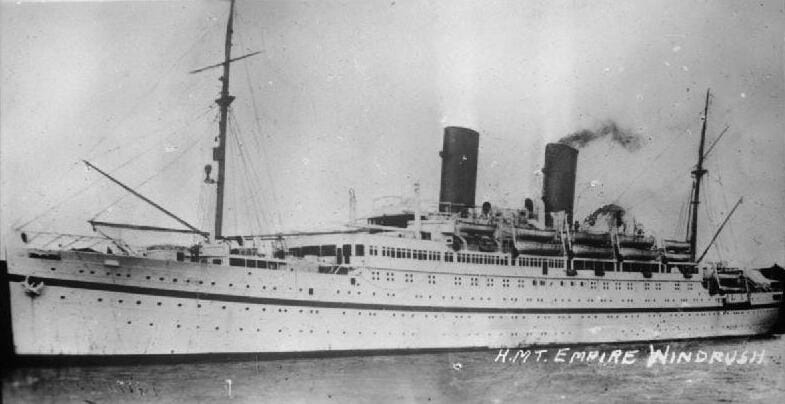

When the HMT Empire Windrush arrived in Tilbury, Essex, in 1948, nobody predicted the massive impact it would have on British music culture.

The British Nationality Act of 1948 gave citizenship to colonial subjects, triggering mass Caribbean migration to the UK through the 1950s and 60s.

Jamaicans arrived in London, Bristol, Birmingham, and other cities, bringing their records, their culture, and their sound systems. They were called the Windrush Generation.

However, British pubs and clubs often refused entry to black patrons. Radio stations would rarely play reggae or ska. There were no platforms for their music, and few spaces where they felt welcome.

So they created their own. Underground networks of sound system parties emerged and spread by word of mouth. Makeshift venues – basements, community centers, private homes – became spaces where Caribbean communities could gather, dance, and maintain cultural connections to Jamaica.

Lloyd Coxsone's Sir Coxsone Outernational became one of the UK's best-known early systems, followed by Jah Shaka, Channel One, Iration Steppas, and Saxon Studio International.

Sound systems became linked to revolt and protest, to which they still are today.

Sound system culture offered safe places for the Windrush Generation

The integration of sound systems into London’s iconic Notting Hill Carnival in 1973 marked a turning point.

Carnival attendees wanted "a Jamaican sound" to balance the Trinidad-dominated steel pan presence. Sound systems became a form of public celebration.

British punk and post-punk bands took notice. The Clash's London Calling features "Revolution Rock," directly channeling reggae's influence.

This built bridges between genres and brought people together under the banner of sound systems.

DJ Kool Herc and Hip-Hop's Jamaican DNA

While sound systems took root in Britain, they were also crossing the Atlantic to New York.

Clive Campbell was born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1955. Growing up in Trenchtown – the same "concrete jungle" that produced Bob Marley and Peter Tosh – young Campbell witnessed dancehall parties thrown by neighborhood sound systems. He was too young to enter, but he'd hang outside, absorbing the music and the culture.

At age 12, his family moved to the Bronx. Campbell, now nicknamed "Hercules" for his muscular physique (later shortened to DJ Kool Herc), started throwing block parties, drawing directly from Jamaican sound system culture.

On August 11, 1973, Herc's sister Cindy threw a back-to-school party in their building's recreation room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue. Cindy needed money for school clothes. Herc provided the music.

That party is now recognized as instrumental in the birth of hip-hop.

Herc and his crew soon brought two crucial innovations from Jamaican sound system culture:

Breakbeat Juggling

Herc noticed dancers went hardest during the instrumental "breaks" in funk and soul records – the short drum solos.

Using two turntables, he'd play two copies of the same record, switching between them to extend the break indefinitely. He called it "The Merry-Go-Round."

Toasting as Rapping

Jamaican DJs (what Americans would call MCs) practiced "toasting" – talking rhythmically over the music, hyping the crowd, calling out friends, boasting about their sound system.

Herc brought this practice to the Bronx, speaking and chanting over his breaks, while his friend Coke La Rock joined him on the mic.

Herc's sound system – dubbed "The Herculoids" – was known for being the loudest in the Bronx, with bass that could be felt blocks away. Pure Jamaican sound system philosophy.

The influence extended beyond Herc. Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmaster Flash, and other pioneering hip-hop DJs all drew from sound system culture.

UK Bass Music: The Second Generation

By the early 1990s, Britain's rave scene was fragmenting and becoming far more diverse and popular.

Breakbeat hardcore was splitting into different directions, and something new was emerging from the collision of UK rave culture and the Jamaican sound system culture that had been simmering in British cities for decades.

Jungle music exploded out of London, Birmingham, and Bristol around 1992-93.

Take the core elements: sped-up breakbeats (often the "Amen break" from The Winstons), chopped and rearranged at 160-180 BPM. Layer in the deep basslines, spatial reverb, and echo techniques from dub.

Add ragga vocals and toasting. The result was jungle – a sound that music writer Simon Reynolds called "Britain's very own equivalent to US hip-hop" and "raved-up, digitised offshoot of Jamaican reggae."

Jungle producers like Goldie, Roni Size, LTJ Bukem, and Shy FX were mostly second-generation Jamaicans and other UK youth who'd grown up around sound system culture.

Jungle quickly developed D'n'B, and soon came dubstep.

Emerging in South London around 2001-2002, dubstep slowed breakbeats right down to 140 BPM or below, combining it with 2-step garage rhythms and – crucially – stripping everything back to accentuate sub-bass.

Digital Mystikz (Mala and Coki), along with Loefah, brought what they called "sound system thinking" to dubstep.

Their label DMZ and their regular nights in Brixton – a part of London already strongly associated with reggae – felt like the natural evolution of Jamaican sound system culture.

Listen to early dubstep tracks like "Anti-War Dub" or anything on the Tempa or DMZ labels and you can hear it.

Grime, which emerged alongside dubstep, inherited the MC tradition from jungle and sound systems.

Free Parties and the Illegal Rave Movement

Sound system culture found another key expression in the UK's illegal rave and free party scene of the early 1990s, which still shapes the underground today.

The Warehouse Days (1988-1992)

When acid house exploded in the late 1980s, warehouse parties started pulling thousands to unauthorized venues outside London's M25 motorway.

The government passed the Entertainment (Increased Penalties) Act in 1990, making illegal raves punishable by fines of up to £20,000 and up to 6 months in prison.

But the crackdown pushed the scene deeper underground – and into direct contact with UK sound system culture.

Sound systems like Spiral Tribe, Bedlam, DiY, and Circus Warp built custom rigs that could be loaded into trucks, driven to remote locations, set up in hours, and torn down just as quickly to stay ahead of police.

Castlemorton and the Crackdown

In May 1992, Castlemorton Common in Worcestershire became the flashpoint.

Multiple sound systems converged for what ballooned into a week-long festival with 20,000-30,000 people, triggering media hysteria and arrests.

The government's response was the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, giving police power to shut down any gathering where music was "wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats."

Of course, that didn’t work either.

The European Teknival Movement

Facing prosecution, Spiral Tribe and other UK sound systems relocated to continental Europe in 1993.

That summer, Spiral Tribe organized the first teknival near Beauvais, France – a multi-day, multi-sound-system gathering that became the template for free party culture across Europe.

CzechTek began in 1994, followed by Frenchtek, Poltek, and Bulgariatek. Desert Storm even brought a teknival to war-torn Sarajevo in 1996, with the front line just ten kilometers away.

"Free tekno" emerged from this scene – hard, fast techno built for outdoor systems, often running at 180+ BPM. The spelling deliberately differentiated it from commercial techno.

An awesome documentary on free tekno

Today, the free party scene continues across the UK and Europe with the same core principles.

Every weekend – summer, winter, rain or shine – you can bet on there being at least one illegal rave or “free party” – somewhere in the UK – from UK Tek in summer to Egg Tek every Easter and more.

Free raves are still common across the UK and Europe

The Legacy Lives On

Jamaican sound system culture gave electronic music its obsession with bass, its understanding of the DJ as artist, its competitive spirit, its remix culture, and its belief that music should be felt physically, not just heard.

This isn't about giving credit where it's due, though that matters. It's about understanding that some of modern music's most powerful ideas came from people working with limited resources, hostile environments, and pure creative necessity.

Sound system culture proved that you don't need expensive studios or industry backing to change music.

You need vision, community, and bass that hits hard enough to shake the ground.

That lesson still holds true today as it ever did.

Looking to build tracks with that bass-heavy foundation? Sample Focus has thousands of bass samples, drum breaks, and dub-influenced loops ready to anchor your productions. Browse the collection and start building.

Comments